The Science and Art of Using Health Behavior Theories Reflectã¢ââ¦

- Inquiry commodity

- Open Access

- Published:

A review of wellness behaviour theories: how useful are these for developing interventions to promote long-term medication adherence for TB and HIV/AIDS?

BMC Public Wellness volume 7, Commodity number:104 (2007) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

Suboptimal treatment adherence remains a barrier to the control of many infectious diseases, including tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS, which contribute significantly to the global disease burden. However, few of the many interventions developed to accost this issue explicitly draw on theories of health behaviour. Such theories could contribute to the design of more constructive interventions to promote handling adherence and to improving assessments of the transferability of these interventions across different health problems and settings.

Methods

This newspaper reviews behaviour change theories applicable to long-term treatment adherence; assesses the evidence for their effectiveness in predicting behaviour change; and examines the implications of these findings for developing strategies to improve TB and HIV/AIDS medication adherence. We searched a number of electronic databases for theories of behaviour change. Eleven theories were examined.

Results

Footling empirical evidence was located on the effectiveness of these theories in promoting adherence. However, several models have the potential to both improve agreement of adherence behaviours and contribute to the blueprint of more effective interventions to promote adherence to TB and HIV/AIDS medication.

Conclusion

Further research and analysis is needed urgently to determine which models might best improve adherence to long-term treatment regimens.

Background

Theories may aid in the design of behaviour change interventions in various ways [1–3], by promoting an understanding of health behaviour, directing research and facilitating the transferability of an intervention from 1 health upshot, geographical expanse or healthcare setting to another.

Ensuring treatment adherence presents a considerable challenge to health initiatives. Haynes et al. ([four], p2) have defined adherence as "the extent to which patients follow the instructions they are given for prescribed treatments". Adherence is a more than neutral term than 'compliance', which can be construed equally being judgmental. While programmes promoting adherence have focused on various health behaviours, this review focuses specifically on long-term adherence to tuberculosis (TB) and HIV/AIDS treatment. Not-adherence to treatment for these diseases has severe human, economic and social costs. Interrupted treatment may reduce treatment efficacy and cause drug resistance [5], resulting in increased morbidity and bloodshed and further infections. Without intervention, adherence rates to long-term medication in high income countries are approximately fifty% [6], while adherence in depression and centre income countries may be even lower [seven].

TB and HIV present item challenges to adherence. Both are chronic and infectious diseases that touch mainly the most disadvantaged populations and involve complex treatment regimens with potentially severe side effects; both are public health priorities and non-adherence may cause drug resistance [7]. These characteristics differentiate these diseases from other chronic diseases such equally asthma and hypertension where, for instance, drug resistance is non a key upshot. Treatment adherence is likewise affected by beliefs about the origins, transmission and treatment of TB and HIV, often resulting in the stigmatisation of those affected [7]. The interaction of these factors make adherence for these diseases not only a priority but a complex wellness issue.

Diverse interventions have been designed to meliorate handling adherence, but few theories draw specifically the processes involved. Currently, there are more 30 psychological theories of behaviour change [viii], making it hard to choose the most appropriate i when designing interventions. This is a detail problem within the field of adherence to long-term medications, where the consequences of non-adherence may exist astringent. Existing theories therefore demand to be examined further to determine their relevance to the issue of long-term medication adherence.

Leventhal and Cameron [9] identified 5 principal theoretical perspectives related to adherence: ane) biomedical; 2) behavioural; three) communication; 4) cognitive; and 5) self-regulatory. Each perspective encompasses several theories. More than recently, the phase perspective has emerged, which includes the transtheoretical model. The most ordinarily used theories are those within the cognitive perspective [1, 10] and the transtheoretical model [1]. This review includes a brusque description of theories within each of the five perspectives listed above, as well as the transtheoretical model. We locate these theories specifically within the realm of adherence to long-term medication, defined as medication regimens of three months or more; depict their key characteristics and evidence base; and examine their relevance and applicability with regard to adherence to long-term medication regimens for TB and HIV/AIDS. To our cognition, the surface area of long-term adherence to medication has non all the same been addressed in reviews of health behaviour theories.

While the focus of this review is on factors affecting consumers, we acknowledge that adherence is a complex and dynamic phenomenon, which relates to consumers, providers, health systems and broader socio-economical and political contexts. Although the theories chosen for this review focus mainly on providers and consumers, this is non the only area in which adherence can be promoted. The review is intended as an information source for those wishing to develop theory-based interventions focusing on intra- or interpersonal factors to increment TB and/or HIV handling adherence.

Methods

A search was performed on MEDLINE, CINAHL, Pre-CINAHL, PsycInfo, ScienceDirect and ERIC databases using the keywords 'health and behaviour and (model or theory)'; '(model or theory); (adherence or concordance or compliance)', from the start date of each database to February 2005. Additional searches were performed in the University of Cape Town library, Google and Google Scholar. Citations were also identified from included papers. Finally, all databases consulted were searched again using the names of theories as keywords, with 'meta-analysis' or 'systematic review' in April 2005. Experts were consulted for comments and references. Published articles or volume chapters in English, describing a particular theory, and articles that presented a meta-analysis of the theory, were included. Manufactures were excluded if they did not satisfy the same criteria. Where possible, interventions related to TB or HIV adherence were identified. No authors were contacted. Several additional randomised controlled studies or other articles were also included as examples of the use of theories in intervention development. In this newspaper we apply the term 'theory', instead of 'model', and the term 'variable', instead of 'construct', when referring to a part of the theory.

Results

Table ane presents the theories included in this commodity and references to meta-analyses synthesizing the testify for each. Below, we summarise each perspective and the theories within it and provide examples of its application to adherence behaviours [come across boosted file 1]. We then examine the usefulness of these theories in developing interventions to promote long-term adherence.

The biomedical perspective

The biomedical perspective incorporates the biomedical theory in which patients are assumed to be passive recipients of doctors' instructions [11]. Wellness or affliction is traced dorsum to biomedical causes, such as bacteria or viruses, and treatment is therefore focused on the patient's body [11]. In keeping with this mechanistic view of illness, mechanical solutions, such as prescribed pills, are preferred [12]; non-adherence is understood to be caused by patient characteristics, such as age and gender [12]. Technological innovations to promote adherence, such as Medication Effect Monitoring Systems ®, are sometimes rooted in this perspective [7]. However, despite its implicit apply by many health professionals, this perspective is infrequently used explicitly in interventions.

A fundamental limitation of this theory is that it ignores factors other than patient characteristics that may touch on health behaviours – for example, patients' perspectives of their own illness [seven]; psycho-social influences [12]; and the impacts of the socio-economic surroundings. The socio-economic environment or demographics may, nonetheless, be markers for other factors that lend themselves to intervention even though they themselves cannot exist inverse [thirteen]. The danger of using demographics equally proxy variables for adherence is that certain groups that come to be seen equally "lost causes" may exist excluded (e.yard. [14]). This biomedical theory has recently been integrated into a larger "biopsycho-socio-environmental" theory, which incorporates the wider socio-environmental context [11]. However, this theory is non located strictly inside the biomedical arroyo. Due to the assumption that patients are passive and the focus on biomedical factors, it is unlikely that the biomedical theory tin contribute significantly to TB or HIV medication adherence. Patients are more often than not active decision makers and practise not merely receive and follow instructions passively. No meta-analyses specifically examining this perspective were identified.

Behavioural (learning) perspective

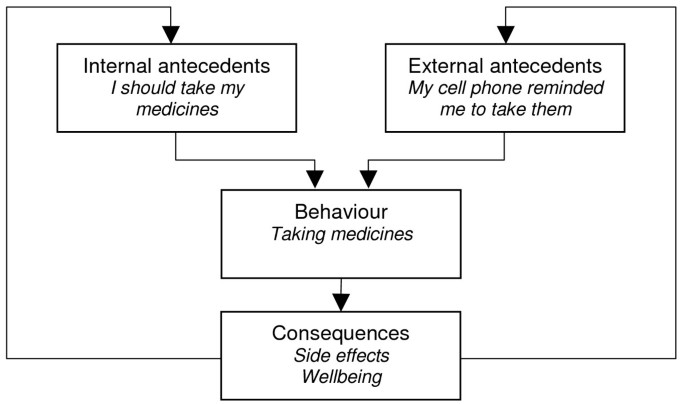

This perspective incorporates behavioural learning theory (BLT) which is focused on the environment and the teaching of skills to manage adherence [7]. It is characterised past the utilise of the principles of antecedents and consequences and their influence on behaviour. Antecedents are either internal (thoughts) or external (environmental cues) while consequences may exist punishments or rewards for a behaviour. The probability of a patient following a specific behaviour will partially depend on these variables [vii].

Behavioural learning theory.

Wellness belief model.

Protection motivation theory.

Revised protection motivation theory.

Social cerebral theory.

Theory of reasoned action.

Theory of planned behaviour.

Information motivation behavioural skills model.

Self regulation theory.

Transtheoretical model.

Adherence promoting strategies informed by this perspective, such as patient reminders, have been found to improve adherence [15]. Several interventions incorporating elements of BLT have also been reported to be constructive for adherence to long-term medications [4]. However, a more recent meta-assay examining adherence to highly active antiretroviral (ARV) therapy concluded that interventions with cue dosing and external rewards – approaches derived from BLT -were as efficacious as those without [xvi]. Another randomised controlled trial on ARVs reported a negative effect when using electronic reminder systems [17]. Further evidence is therefore needed on the effectiveness of these types of strategy.

BLT has been critiqued for lacking an individualised approach and for non considering less conscious influences on behaviour not linked to immediate rewards [12]. These influences include, for example, past behaviour, habits, or lack of acceptance of a diagnosis. The theory is express, too, by its focus on external influences on behaviour. Programme planners should therefore consider carefully individuals' perceptions of appropriate rewards before using such theory to inform programme design. Interventions cartoon on behavioural theory are oftentimes used in combination with other approaches, although seldom explicitly. No meta-analyses were found that examined this perspective.

Communication perspective

Communication is said to be "the cornerstone of every patient-practitioner relationship" [[11], p. 56]. This perspective suggests that improved provider-client communication will enhance adherence [7, 11] and implies that this tin be achieved through patient instruction and good health care worker communication skills – an approach based on the notion that communication needs to exist clear and comprehensible to be effective. It besides places emphasis on the timing of treatment, education and comprehension. An example of an intervention utilising this perspective is one that aims to improve client-provider interaction. Critiques of this perspective fence that information technology ignores attitudinal, motivational and interpersonal factors that may interfere with the reception of the bulletin and the translation of cognition into behaviour change [12].

A number of reviews have examined the effects of interventions including communication elements [18–21]. However, few of these have examined the effects of advice on health behaviours specifically. Two reviews focusing on interventions to improve provider-customer communication showed that these tin amend communication in consultations, patient satisfaction with care [xviii] likewise as health outcomes [21]. However, these reviews also show limited and mixed evidence on the effects of such interventions on patient health care behaviours, such as adherence.

Advice components have been used within several adherence interventions but seldom explicitly or equally the main component. Such interventions are unlikely to succeed in isolation in improving long-term adherence to medications considering of the influence of external factors, such equally the costs of accessing healthcare for handling. Advice interventions are also typically restricted to provider-customer interactions and boosted social or financial back up may thus be required.

Cognitive perspective

The cognitive perspective includes theories such as the wellness conventionalities model (HBM), social-cognitive theory (SCT), the theories of reasoned action (TRA) and planned behaviour (TPB) and the protection motivation theory (PMT). These theories focus on cognitive variables as part of behaviour modify, and share the assumption that attitudes and beliefs [22], also as expectations of hereafter events and outcomes [23], are major determinants of wellness related behaviour. In the face up of various alternatives, these theories propose, individuals will choose the activeness that volition lead most probable to positive outcomes.

These theories accept noticeable weaknesses, nonetheless: firstly, that non-voluntary factors can impact behaviour [23]; devoting time to conscious deliberation regarding a repeated selection also seems uneconomical [22]. Secondly, these theories practice not adequately address the behavioural skills needed to ensure adherence [seven]. Thirdly, these theories give little attention to the origin of beliefs and how these behavior may influence other behaviours [24]. In addition, information technology has been argued that they ignore other factors that may touch on on adherence behaviour, such as ability relationships and social reputations [25], and the possibility that risk behaviour may involve more than one person [26]. Information technology has as well been suggested that they focus on a single threat and prevention behaviour and do not include possible additional threats competing for the individual's attention [24].

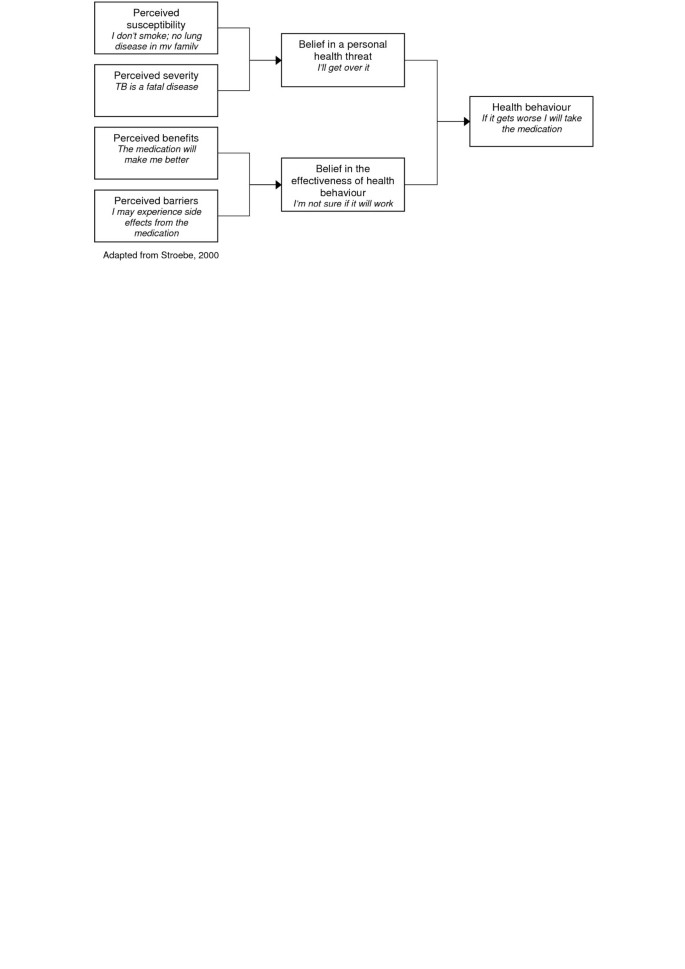

Health Belief Model

The HBM views health behaviour change as based on a rational appraisal of the rest betwixt the barriers to and benefits of action [12]. According to this model, the perceived seriousness of, and susceptibility to, a disease influence individual's perceived threat of disease. Similarly, perceived benefits and perceived barriers influence perceptions of the effectiveness of health behaviour. In plow, demographic and socio-psychological variables influence both perceived susceptibility and perceived seriousness, and the perceived benefits and perceived barriers to action [1, 7]. Perceived threat is influenced by cues to action, which can be internal (e.one thousand. symptom perception) or external (eastward.thousand. health communication) (Rosenstock, 1974 in [7]).

High-perceived threat, low barriers and high perceived benefits to activeness increment the likelihood of engaging in the recommended behaviour [27]. Mostly, all of the model'southward components are seen as independent predictors of health behaviour [28]. Bandura [29] notes, nevertheless, that perceived threats – specially perceived severity – accept a weak correlation with health activeness and might even result in avoidance of protective action. Perceived severity may also non be as important equally perceived susceptibility. Recently, self-efficacy was added into the theory [30], thereby incorporating the need to feel competent before effecting long-term change [31].

In that location are two main criticisms of this theory: firstly, the relationships between these variables have not been explicitly spelt out [32] and no definitions accept been constructed for the individual components or articulate rules of combination formulated [28]. Information technology is assumed that the variables are not moderated by each other and take an condiment effect [32]. If, for example, perceived seriousness is high and susceptibility is low, it is still assumed that the likelihood of activeness will exist high -intuitively i might assume that the likelihood in this case would be lower than when both of the variables are high [22, 32]. The HBM also assumes that variables touch wellness behaviour straight and remain unmoderated by behavioural intentions [22]. The second major weakness of HBM is that important determinants of health behaviour, such equally the positive furnishings of negative behaviours and social influence, are non included [22, 32]. In addition, some behaviours such as smoking are based on habits rather than decisions [33]. While the theory may predict adherence in some situations, it has not been plant to practise and so for "risk reduction behaviours that are more linked to socially determined or unconscious motivations" [[12], p.165].

The two reviews identified that examined this theory had inconclusive results. A critical review [34] examined 19 studies which involved sick role behaviours, such as compliance to antihypertensive medication. While the 4 dimensions of the model produced pregnant effects in most of the studies included [34], the studies had considerable methodological gaps. A more contempo meta-analysis [35] indicated that while the HBM was capable of predicting ten% of variance in behaviour at all-time, the included studies were heterogeneous and were unable to support conclusions every bit to the validity of the model. Therefore further studies are needed to assess the validity of this theory. When applying this theory to long-term medication adherence, it is besides important for the influence of socio-psychological factors to exist considered. For example, cultural beliefs almost TB – such every bit its relationship with witchcraft [36] – may reduce an adherence intervention'southward effectiveness.

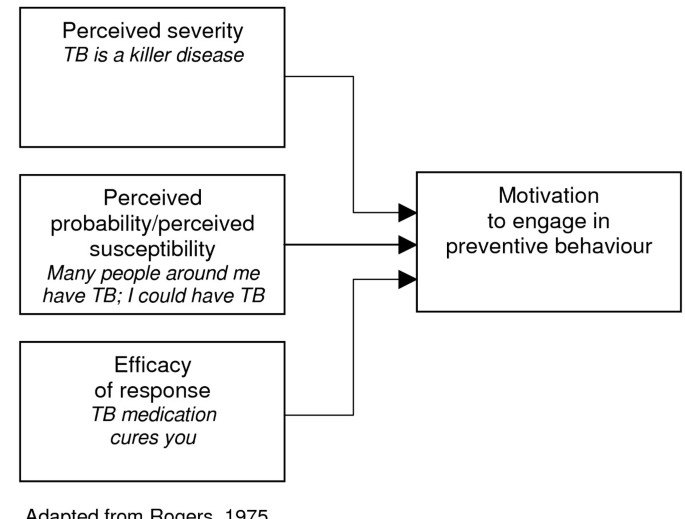

The protection-motivation theory

According to this theory, behaviour modify may exist achieved past appealing to an individual's fears. Three components of fright arousal are postulated: the magnitude of impairment of a depicted outcome; the probability of that effect'due south occurrence; and the efficacy of the protective response [37]. These, information technology is contended, combine multiplicatively to determine the intensity of protection motivation [22], resulting in action occurring equally a effect of a desire to protect oneself from danger [37]. This is the only theory within the broader cognitive perspective that explicitly uses the costs and benefits of existing and recommended behaviour to predict the likelihood of change [23].

An of import limitation of this theory is that not all environmental and cognitive variables that could touch on on attitude change (such as the pressure to adapt to social norms) are identified [37]. The about recent version of the theory assumes that the motivation to protect oneself from danger is a positive linear function of beliefs that: the threat is severe, one is personally vulnerable, 1 can perform the coping response (self efficacy) and the coping response is constructive (response efficacy) [22]. Beliefs that health-impairing behaviour is rewarding but that giving it up is costly are causeless to take a negative effect [22]. All the same, the subdivision of perceived efficacy into categories of response and self efficacy is mayhap inappropriate – people would not consider themselves capable of performing an action without the means to do information technology [29].

A meta-assay examining this theory constitute simply moderate effects on behaviour [39]. The revised PMT may be less cumbersome to apply than the TRA – it besides does non presume that behaviour is always rational. [39]. The PMT may be advisable for adherence interventions as it is unlikely that an individual consciously re-evaluates all of their routine behaviours such as, for example, taking long-term medication. However, the influence of social, psychological and environmental factors on motivation requires consideration by those using this arroyo.

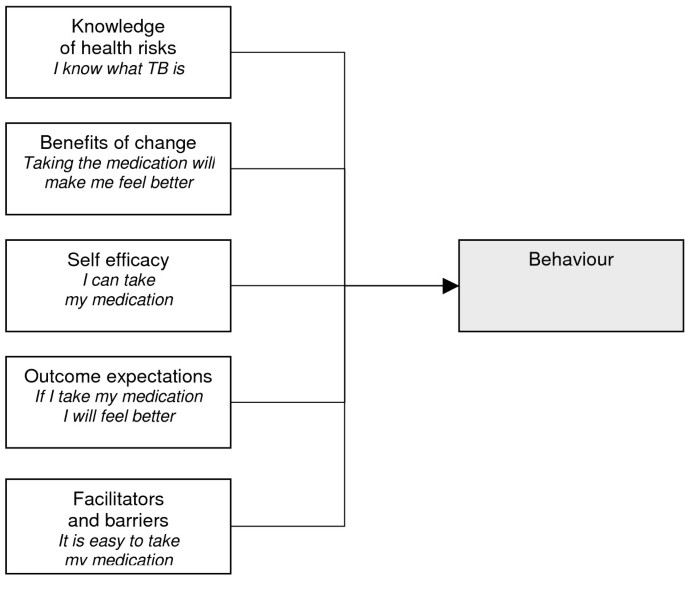

Social-cognitive theory

This theory evolved from social learning theory and may exist the most comprehensive theory of behaviour alter developed thus far [1]. It posits a multifaceted causal construction in the regulation of human being motivation, activeness and well-being [40] and offers both predictors of adherence and guidelines for its promotion [29]. The bones organising principle of behaviour change proposed by this theory is reciprocal determinism in which there is a continuous, dynamic interaction betwixt the individual, the environment and behaviour [i].

Social-cognitive theory suggests that while knowledge of health risks and benefits are a prerequisite to change, additional self-influences are necessary for change to occur [41]. Beliefs regarding personal efficacy are amid some of these influences, and these play a fundamental office in change. Health behaviour is also affected by the expected outcomes – which may exist the positive and negative furnishings of the behaviour or the textile losses and benefits. Outcomes may also be social, including social approval or disapproval of an activeness. A person'southward positive and negative self-evaluations of their health behaviour and wellness status may as well influence the upshot. Other determinants of behaviour are perceived facilitators and barriers. Behaviour modify may be due to the reduction or elimination of barriers [41]. In sum, this theory proposes that behaviours are enacted if people perceive that they accept command over the effect, that at that place are few external barriers and when individuals have conviction in their ability to execute the behaviour [28].

A review reported that cocky efficacy could explicate between 4% and 26% of variance in behaviour [42]. However, this analysis was limited to studies of practice behaviour, and did not include reports that examined SCT as a whole. Due to its wide-ranging focus, this theory is difficult to operationalise and is often used only in office [43], thus raising questions regarding its applicability to intervention development.

Theory of planned behaviour and the theory of reasoned activeness

The first work in this area was on the TRA [44].

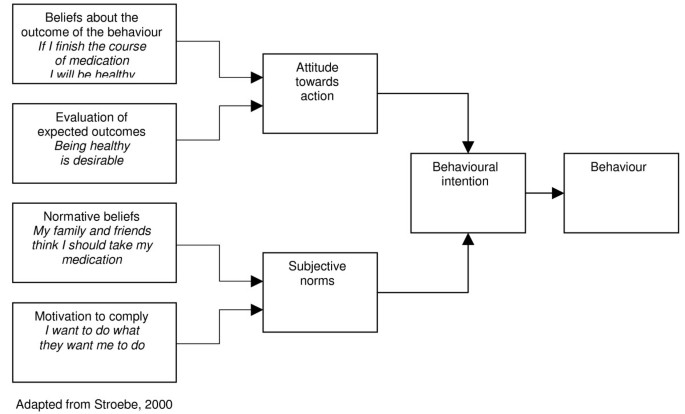

The TRA assumes that most socially relevant behaviours are nether volitional control, and that a person's intention to perform a particular behaviour is both the immediate determinant and the single all-time predictor of that behaviour [45]. An intention to perform a behaviour is influenced past attitudes towards the action, including the individual's positive or negative beliefs and evaluations of the event of the behaviour. It is likewise influenced by subjective norms, including the perceived expectations of important others (eastward.g. family or work colleagues) with regard to a person'due south behaviour; and the motivation for a person to comply with others' wishes. Behavioural intention, it is contended, so results in action [44]. The authors argue that other variables besides those described above tin can only influence the behaviour if such variables influence attitudes or subjective norms. A meta-assay examining this theory constitute that it could explicate approximately 25% of variance in behaviour in intention lone, and slightly less than 50% of variance in intentions [45]. This suggests that back up for this theory is limited.

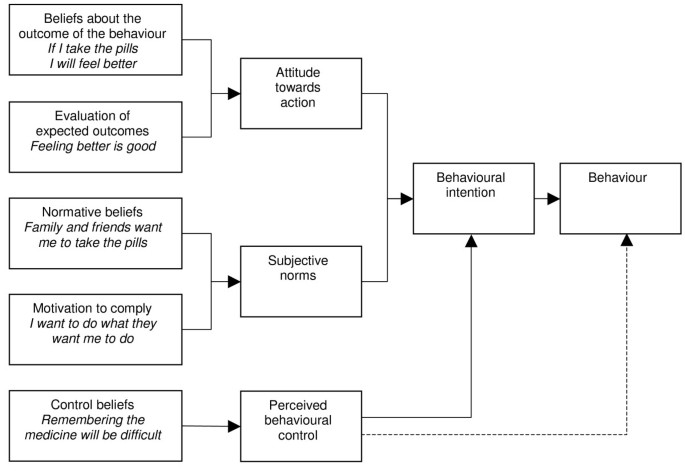

Additionally, The TRA omits the fact that behaviour may not always be under volitional command and the impacts of by behaviour on current behaviours [22]. Recognising this, the authors extended the theory to include behavioural command and termed this the TPB. 'Behavioural control' represents the perceived ease or difficulty of performing the behaviour and is a part of control beliefs [45]. Conceptually it is very similar to self-efficacy [22] and includes noesis of relevant skills, experience, emotions, past rails record and external circumstances (Ajzen, in [46]). Behavioural control is assumed to have a straight influence on intention [45]. Meta-analyses examining the TPB have constitute varied results regarding the effectiveness of the theory'southward components [47–49]. Although not conclusive, the results of the analyses are promising.

Sutton [45] suggests that the TRA and TPB require more conceptualisation, definition and boosted explanatory factors. Attitudes and intentions can also be influenced past a diversity of factors that are not outlined in the to a higher place theories [22]. Specifically, these theories are largely dependent on rational processes [50] and do not allow explicitly for the impacts of emotions or religious beliefs on behaviour, which may be relevant to stigmatised diseases like TB and HIV/AIDS.

Information-motivation-behavioural skills (IMB) theory

This theory was developed to promote contraceptive use and prevent HIV transmission. IMB was synthetic to exist conceptually based, generalisable and simple [51]. Information technology has since been tailored specifically to designing interventions to promote adherence to Art [52]

This theory focuses on 3 components that effect in behaviour change: information, motivation and behaviour skills. Information relates to the basic cognition about a medical condition, and is an essential prerequisite for behaviour alter but not necessarily sufficient in isolation [51]. A favourable intervention would establish the baseline levels of information, and target data gaps [51]. The second component, motivation, results from personal attitudes towards adherence; perceived social back up for the behaviour; and the patients' subjective norm or perception of how others with the condition might behave [7]. Finally, behavioural skills include factors such every bit ensuring that the patient has the skills, tools and strategies to perform the behaviour equally well as a sense of cocky-efficacy – the belief that they can attain the behaviour [51].

The components mentioned above need to be direct relevant to the desired behaviour to be effective [7]. They can besides be moderated by a range of contextual factors such as living weather condition and access to wellness services [52]. Information and motivation are thought to actuate behavioural skills, which in turn result in risk reduction behavioural change and maintenance [51]. The theory is said to be moderately effective in promoting behaviour change [7], and has been shown to have predictive value for Art adherence [53]. Withal, no meta-analyses were identified that assessed the furnishings of this model. The reward of IMB is its simplicity and its contempo application to ART adherence suggests that it may be a promising model for promoting adherence to TB medication.

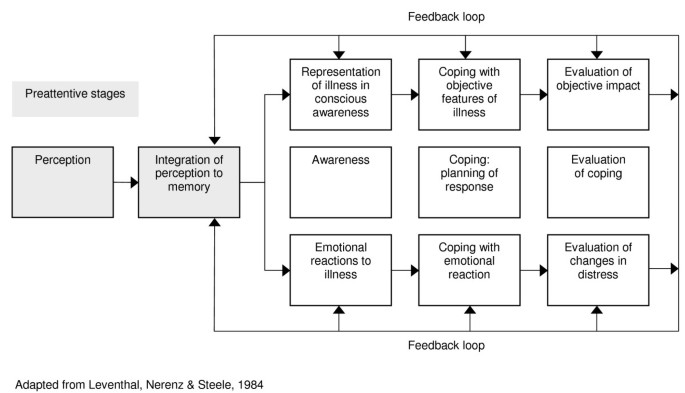

Self-regulation perspectives

Self-regulatory theory is the master theory in this domain. Developed to conceptualise the adherence process in a style that re-focuses on the patient [54], the theory proposes that it is necessary to examine individuals' subjective feel of health threats to understand the way in which they adapt to these threats. Co-ordinate to this theory, individuals form cognitive representations of health threats (and related emotional responses) that combine new data with past experiences [55]. These representations 'guide' their choice of particular strategies for coping with health threats, and consequently influence associated outcomes [56]. The theory is based on the assumption that people are motivated to avert and care for affliction threats and that people are active, self-regulating trouble solvers [57]. Individuals, it is implicitly assumed, will endeavor to reach a state of internal equilibrium through testing coping strategies. The process of creating health threat representations and choosing coping strategies is causeless to exist dynamic and informed by an individual's personality, and religious, social and cultural context [55]. In improver, a complex interplay exists betwixt environmental perceptions, symptoms and beliefs about disease causation [54].

The cocky-regulation theory offers little guidance related to the design of interventions [vii] and no meta-analyses examining evidence for the effectiveness of this theory were identified. While the theory seems intuitively advisable, specific suggestions are needed as to how these processes could promote adherence.

Stage perspectives

The transtheoretical model (TTM)

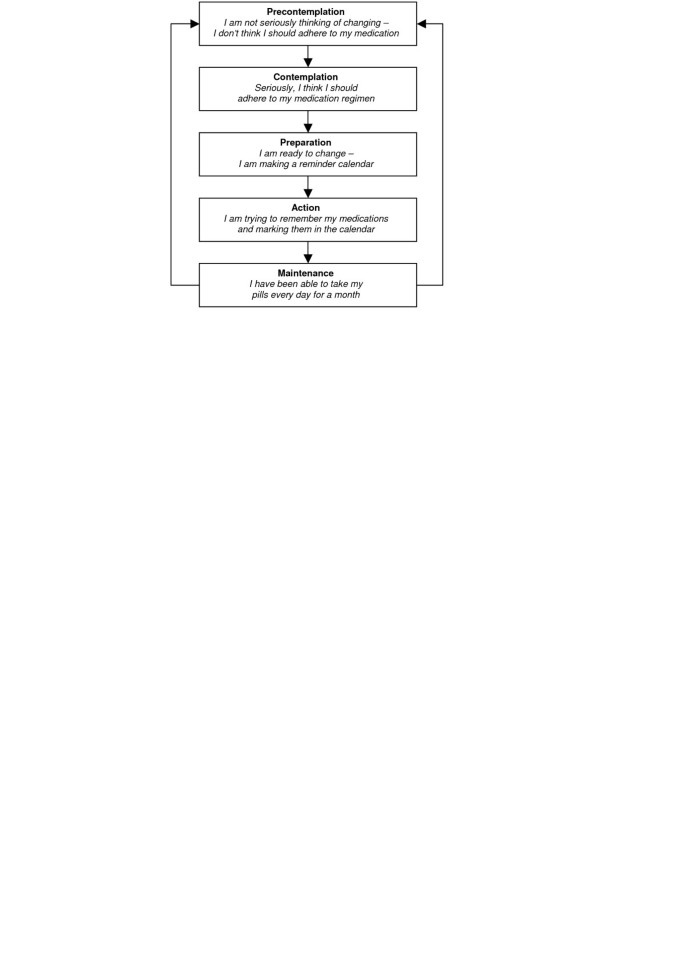

This theory is most prominent among the phase perspectives. Information technology hypothesizes a number of qualitatively different, discrete stages and processes of change, and reasons that people motion through these stages, typically relapsing and revisiting earlier stages before success [58, 59]. This theory is said to offering an "integrative perspective on the construction of intentional change" [[60], p. 1102] – the perceived advantages and disadvantages of behaviour are crucial to behaviour change [61].

The procedure of change includes independent variables that assess how people modify their behaviour [62] and the covert and overt activities that help individuals towards healthier behaviour [63]. Different processes are emphasised at different stages.

Criticisms of TTM include the stages postulated and their coverage and definitions, and descriptors of alter. Co-ordinate to Bandura [40], this theory violates all three of the basic assumptions of phase theories: qualitative transformations across discrete stages, invariant sequence of change, and not-reversibility. In addition, the proposed stages may only be different points on a larger continuum [29, 58, 63]. Bandura [29] suggests that human functioning is too multifaceted to fit into carve up, discrete stages and argues that stage thinking could constrain the scope of modify-promoting interventions. Furthermore, TTM provides little information on how people alter and why but some individuals succeed [28].

Sutton [56] argues that the stage definitions included in the TTM are logically flawed, and that the time periods assigned to each stage are arbitrary. Similarly, there is also a need for more attention to measurement, testing issues and definition of variables and causal relationships [58]. The coverage and blazon of processes included may besides exist inadequate [63].

The TTM has received much practitioner back up over the years, but less direct inquiry support for its efficacy [3, 10]. The meta-analyses identified for this review did non offering direct support for the theory; while ane found that individuals use all 10 processes of change [64], another found that interventions that used the stage perspective were not more than efficient than those not using the theory [65]. Further evidence of its efficacy is therefore needed. A strength of this theory is that it allows interventions to be tailored to individual needs. Even so, large-calibration implementation of these interventions may exist time consuming, complicated and costly. Its use may exist more than appropriate in areas where rapid behaviour alter is non necessary.

Discussion

This review has discussed a number of health behaviour theories that contribute to understanding adherence to long-term medications, such equally those for TB and HIV/AIDS.

Although the use of theory to develop interventions to promote adherence offers several advantages, it also has some limitations. Firstly, there is little evidence that allows for the straight comparison of these theories [66]. Combining studies based on even one theory, in gild to perform a meta-analysis to assess its effectiveness in predicting behaviours, is difficult due to various methodological issues in the original studies [sixty]. Furthermore, the number of theories in this field has proliferated over time, as theorists accept examined dissimilar areas of behaviour and engaged in re-examining existing explanatory theories. Researchers, wellness planners and practitioners may therefore be overwhelmed past the multitude of theories available to them and the fragmented, and often contradictory, evidence. Questions also remain regarding the applicability of these theories to contexts other than those in which they were developed. Ashing-Giwa [67], for instance, suggests that the higher up theories practice not accost socio-cultural aspects sufficiently. Issues such as the stigma fastened to TB due to its perceived relation to HIV (peculiarly in developing countries) may bear upon on the acceptability and the uptake of interventions. Farther attention should therefore be given to the question of whether theories adult in the Usa and the UK are applicable to individuals in other contexts where the disease burden from HIV/AIDS and TB is greatest.

Secondly, health behaviour change theories have tended to encompass a wide diversity of health behaviours, each qualitatively unlike. The systematic reviews identified for this paper included studies ranging from smoking cessation to mothers limiting babies' sugar intake. Item theories may be more than applicable than others to improving adherence to specific wellness behaviours. For example, adherence to long-term medication will necessarily be dissimilar to a behaviour modify required to accept upward exercise. In add-on, achieving adherence to TB medication may be seen as an urgent event for public health because of its infectiousness, and the recent emergence of extremely drug resistant strains [68]. It is hard therefore to compare the effects of the theories across wellness categories or even inside individual categories.

Thirdly, few studies were identified that had examined the selected health behaviour theories in relation to long-term medication adherence, or that had developed interventions to promote long-term adherence explicitly based on these theories, particularly for TB. Sumartojo's [xiii] assessment that a theory-based approach has largely been absent within the field of TB behavioural research appears to remain valid today.

The awarding of theories to the design of interventions remains a challenge for researchers and programme planners [69] and at that place is considerable fence concerning the effectiveness and usefulness of theory in informing intervention development (run into [two, seventy, 71]). Despite a variety of studies in a diverseness of fields, or peradventure because of this variation, we would argue that in that location is no clear bear witness nevertheless for the support of any of these theories within the field of adherence behaviours. This is not to say that these theories cannot exist useful – rather, nosotros accept insufficient evidence to conclusively decide this.

While these discussions proceed, research should aim to shed calorie-free on the key questions related to the theory-intervention debate: Do sound theories upshot in effective interventions? Does an constructive intervention constitute proof of a theory'southward value? How might theory exist used to inform the design of an effective intervention? And how tin can a theory be reliably tested? Some research work has already been undertaken in these areas: in a systematic review of antiretroviral handling adherence interventions, Amico et al. [72] found that the use of theory in amalgam an intervention did not account for variability in the intervention's efficacy. Yet, it is unclear how many of the 24 included studies in this review articulated a health behaviour change theory or the extent to which this was done.

Ii possible approaches have been suggested to addressing the difficulties raised by the multitude of existing theories on wellness behaviour change. One approach is to attempt to identify variables common to these theories. This has been undertaken for 33 health behaviour change theories [7] in order to make psychological theories more accessible and easier to select. The results of this report provide some guidance on the most important variables in psychological theories, and may assistance in the farther development of wellness behaviour change theories. A second approach is to attempt to integrate the theories. While there is a need for such theoretical integration [73], we argue that researchers and theorists alike should be cautious when picking and choosing parts of other theories to develop farther theories – and so-chosen "cafeteria-manner theorizing" – equally the resulting theories may include redundant variables [[29], p. 285].

Because some theories share overlapping variables describing using different names [8, 41], and most differences are due to an emphasis of one variable over some other [1], it would serve the evolution of this field to conduct studies to identify particular variables that perform all-time in predicting behaviour alter. For example, in a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials testing antiretroviral treatment adherence interventions, Simoni [sixteen] establish that giving basic information to patients, and engaging them in word about helping them to overcome cerebral factors, lack of motivation and unrealistic expectations well-nigh adherence, were effective in improving adherence. Similarly, comparative studies betwixt theories could exist used to identify constructive components [74]. The field of health behaviour theory remains dynamic, and it is important to go along developing existing theories and approaches as new bear witness emerges.

Applying wellness behaviour theories to medication adherence for TB and HIV/AIDS

How optimal adherence for TB and HIV/AIDS can exist ensured remains an important question. While large numbers of studies have explored patients' and health care providers' views regarding adherence to TB treatment [75] or have described programmes to meliorate adherence to these medications, there are yet relatively few rigorous evaluations of interventions to promote adherence to TB and HIV/AIDS treatments [76, 77]; even fewer take explicitly utilised behaviour modify theories. For example, a systematic review of interventions to promote adherence to TB treatment [77] included 10 trials, none of which used an explicit theoretical framework. A similar review identified vii different randomised controlled trials of interventions to promote adherence to antiretroviral therapy [76], of which only one employed an explicit theoretical framework. Similar figures have been reported in other domains: a review of guideline implementation studies showed that less than x% of these provided an explicit theoretical rationale for their intervention [78]. Given the paucity of evidence to support any item wellness behaviour theory, we cannot therefore suggest that these theories be used routinely to pattern adherence promoting interventions. Notwithstanding, since these theories may well have practical behaviour change potential, and since the problem of medication adherence remains pregnant for both clinical medicine and public wellness, further exploratory and explanatory inquiry is needed.

A number of recommendations emerge from this review (Table 2): firstly, future research should focus not on the development of new theories but rather on the further test of those already elaborated. Several key attributes that should be encompassed past theories explaining behaviour modify have been suggested, including demonstrated effectiveness in predicting and explaining changes in behaviour across a range of domains; an ability to explain behaviour using modifiable factors; and an ability to generate clear, testable hypotheses. The theories should include non-volitional components (i.e. issues over which individuals practise not have consummate control) and take into account the influence of external factors, as perceived past individuals [2, seventy].

Secondly, further piece of work is required to place theories of health behaviour that are most applicative to improving adherence to long-term medication. Existing health behaviour theories should be tested systematically to establish which all-time predict effects on different kinds of behaviour for different groups of people in dissimilar contexts. For example, does a item theory predict changes in adherence behaviour for both men and women with TB in both England and Due south Africa? Some researchers have argued that experimental enquiry and increased clarity in theories and methods could assist in the identification of constructive behaviour alter techniques, thereby contributing to the development of testify-based practice in health psychology and implementation research [2, 3]. Similar efforts need to be made regarding the use of theories as applied to adherence behaviour.

Thirdly, the abundance of theories and their poor evidence base highlights the need to develop and trial interventions that use these theories appropriately (i.e. in concordance with the theory), with well defined and operationalised variables. This will assist to accelerate the study of human adherence behaviour and allow for better informed decisions related to how to these theories could be more than widely applied in practice. (Run into references [2] and [75] for guidance on developing theoretically informed interventions). Nosotros have compiled a number of examples [meet additional file 1] of the application of such theories in practice.

Finally, reports of interventions to promote adherence to long-term medications for other health issues, such as diabetes, asthma and hypertension, should be reviewed to determine how many have drawn on theory in the design and testing of these interventions; the range of theories utilised and the means in which this was washed; and the ways in which the employ of theory contributed to understanding the furnishings of these interventions. Many reviews of such interventions exist (for example, see [83, 84]) and these could act as a starting point for such work.

It is also of import to list some of the limitations of this review. Firstly, we take been unable to capture all the bachelor data on tests of health behaviour theories. Secondly, this paper examines only theories constructed by researchers and does not explore the health theories held by those receiving treatment. These lay theories of adherence with regard to antiretroviral [81] and TB treatment [75] are discussed elsewhere.

It should also be noted that any understanding of individual health behaviour, and interventions to change this, must be located inside the relevant social, psychological, economic and physical environments [28]. Much research on adherence to TB medication has indicated that poor adherence is commonly the result of factors outside the individual's control, including clinic and wellness care organisation factors (such equally interruptions to drug supply and long distances to health facilities) and structural factors (such as poverty and migration) [thirteen, 82, 83]. Similar issues take been reported for adherence to Fine art [84]. Any focus on irresolute the behaviours of individuals with TB or HIV should non issue in the neglect of these other dimensions or the further disadvantaging of the poor and vulnerable, thereby widening health disparities. Interventions that focus on providers, the provider-patient relationship, health system and contextual factors therefore also need to be developed and evaluated [76].

Conclusion

There is no uncomplicated solution to the problem of adherence, or to the area of behaviour change. Health behaviour theories may shed calorie-free on the processes underlying behaviour change. However, an explicit theoretical basis is not e'er necessary for a successful intervention and further examination is needed to determine whether theory-based interventions in health care are more effective than those without an explicit theoretical foundation [two, lxx]. This review contributes to advancing this field by describing the commonly cited health behaviour theories, presenting the testify and critique for each; discussing the applicability of these theories to adherence behaviour; and highlighting several recommendations for enquiry and theory development. To sympathise and overcome the barriers to treatment adherence, considerable research is needed. Withal, given the importance of long-term medication adherence to global public wellness, particularly in relation to the HIV and TB epidemics, such enquiry should receive much college priority.

Abbreviations

- HIV/AIDS:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus/Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

- TB:

-

Tuberculosis

- ARV:

-

Antiretroviral

- SCT:

-

Social-cognitive theory

- TRA:

-

Theory of reasoned action

- PMT:

-

Protection motivation theory

- HBM:

-

Health belief model

- TPB:

-

Theory of planned behaviour

- IMB:

-

Information-motivation-behavioural skills model

- Fine art:

-

Antiretroviral therapy

- TTM:

-

Transtheoretical model

References

-

Redding CA, Rossi JS, Rossi SR, Velicer WF, Prochaska JO: Health behaviour models. Int Electr J Wellness Educ. 2000, iii: 180-193. [http://www.oiiq.org/SanteCoeur/docs/redding_iejhe_vol3_nospecial_2000.pdf]

-

Eccles K, Grimshaw J, Walker A, Johnston M, Pitts N: Changing the behavior of healthcare professionals: The apply of theory in promoting the uptake of research findings. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005, 58: 107-112. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.09.002.

-

Michie S, Abraham C: Interventions to change health behaviours: Show-based or evidence-inspired?. Psychol Health. 2004, xix: 29-49. 10.1080/0887044031000141199.

-

Haynes RB, McDonald H, Garg AX, Montague P: Interventions for helping patients to follow prescriptions for medications. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002, CD000011-2

-

Raviglione M, Snider D, Kochi A: Global epidemiology of tuberculosis: Morbidity and mortality of a worldwide epidemic. J Am Med Assoc. 1995, 273: 220-226. x.1001/jama.273.3.220.

-

Sackett DL, Snow JC: The magnitude of adherence and non-adherence. Compliance in Wellness Intendance. Edited by: Haynes RB, Taylor DW, Sackett DL. 1979, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 11-22.

-

World Health Organization: Adherence to long-term therapies: Prove for activeness. Geneva. 2003

-

Michie S, Johnston One thousand, Abraham C, Lawton R, Parker D, Walker A: Making psychological theory useful for implementing show based practice: A consensus approach. Qual Saf Health Intendance. 2005, 14: 26-33. x.1136/qshc.2004.011155.

-

Leventhal H, Cameron L: Behavioural theories and the problem of compliance. Patient Educ Couns. 1987, 10: 117-138. 10.1016/0738-3991(87)90093-0.

-

Brawley LR, Culos-Reed SN: Studying adherence to therapeutic regimens: Overview, theories, recommendations. Control Clin Trials. 2000, 21: 156S-163S. 10.1016/S0197-2456(00)00073-eight.

-

Ross Eastward, Deverell A: Psychosocial approaches to health, disease and disability: A reader for health care professionals. 2004, Pretoria: Van Schaik

-

Blackwell B: Compliance. Psychotherapy and psychosomatics. 1992, 58: 161-169.

-

Sumartojo Eastward: When tuberculosis treatment fails: A social behavioural account of patient adherence. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993, 147: 1311-1320.

-

Singh V, Jaiswal A, Porter JDH, Ogden JA, Sarin R, Sharma PP, Arora VK, Kain RC: TB control, poverty and vulnerability in Delhi, India. Trop Med Int Wellness. 2002, 7: 693-700. 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2002.00909.x.

-

Dunbar JM, Marshall GD, Hovell MF: Behavioural strategies for improving compliance. Compliance in health intendance. Edited past: Haynes RB, Taylor DW, Sackett DL. 1979, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 174-190.

-

Simoni JM, Pearson CR, Pantalone DW, Marks Chiliad, Crepaz N: Efficacy of interventions in improving highly active antiretroviral therapy adherence and HIV-ane RNA viral load: a meta-analytic review of randomized controlled trials. J Acquir Allowed Defic Syndr. 43 (Suppl 1): S23-S35. 2006 Dec 1

-

Mannheimer SB, Morse East, Matts JP, Andrews Fifty, Child C, Schmetter B, Friedland GH: Sustained do good from a long-term antiretroviral adherence intervention : results of a large randomized clinical trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 43 (Suppl 1): S41-S47. 2006 Dec i

-

Lewin SA, Skea ZC, Entwistle V, Zwarenstein M, Dick J: Interventions for providers to promote a patient-centred approach in clinical consultations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001, 4: CD003267-

-

Murray E, Burns J, See Tai S, Lai R, Nazareth I: Interactive Health Communication Applications for people with chronic disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005, 4: CD004274-

-

McKinstry B, Ashcroft RE, Automobile J, Freeman GK, Sheikh A: Interventions for improving patients' trust in doctors and groups of doctors. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006, three: CD004134-

-

Griffin SJ, Kinmonth A, Veltman MWM, Gillard S, Grant J, Stewart M: Effect on Health-Related Outcomes of Interventions to Alter the Interaction Between Patients and Practitioners: A Systematic Review of Trials. Ann Fam Med. 2004, 2: 595-608. 10.1370/afm.142.

-

Stroebe Due west: Social psychology and health. 2000, Buckingham: Open up University Press, 2

-

Gebhardt WA, Maes Due south: Integrating social-psychological frameworks for health behaviour enquiry. Am J Health Beh. 2001, 25: 528-536.

-

Weinstein ND: The precaution adoption procedure. Health Psychol. 1988, 7: 355-386. 10.1037/0278-6133.7.4.355.

-

Ingham R, Woodcock A, Stenner K: The limitations of rational decision-making models as applied to young people's sexual behaviour. AIDS: Rights, risk and reason. Edited by: Aggleton PP, Davies P, Hart Thousand. 1992, London: Falmer Printing, 163-173.

-

Bloor M: A user's guide to contrasting theories of HIV related risk behaviour. In Medicine, health and risk: Sociological approaches (Sociology of Wellness and Disease Monograph Serial). Edited by: Gabe J. 1995, London: Blackwell Publishers, 19-30.

-

Becker MH, Maiman LA, Kirscht JP, Haefner DP, Drachman RH, Taylor DW: Patient perceptions and compliance: Contempo studies of the Health Belief Model. Compliance in Health Care. Edited by: Haynes RB, Taylor DW, Sackett DL. 1979, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 78-109.

-

Armitage CJ, Conner M: Social cognition models and health behaviour: A structured review. Psychol Health. 2000, 15: 173-189.

-

Bandura A: Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. 1997, New York: W. H. Freeman and Company

-

Rosenstock IM, Strecher VJ, Becker MH: Social learning theory and the health belief model. Health Educ Q. 1988, 15: 175-183.

-

Strecher V, Rosenstock I: The health belief model. Cambridge Handbook of psychology, health and medicine. Edited by: Baum A, Newman S, Weinman J, West R, McManus C. 1997, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 113-116.

-

Stroebe West, de Wit J: Health impairing behaviours. Applied Social Psychology. Edited by: Semin GR, Fiedler K. 1996, London: Sage, 113-143.

-

Rosenstock IM: The wellness conventionalities model: Explaining health behavior through expectancies. Wellness behaviour and health pedagogy. Edited past: Glanz K, Lewis FM, Rimer BK. 1990, San Francisco: Josey-Bass, 39-62.

-

Janz NK, Becker MH: The wellness belief model: A decade later. Wellness Educ Q. 1984, 11: i-47.

-

Harrison JA, Mullen PD, Green LW: A meta-assay of studies of the health conventionalities model with adults. Health Educ Res. 1992, 7: 107-116. x.1093/her/7.one.107.

-

De Villiers S: Tuberculosis in anthropological perspective. South African Journal of Ethnology. 1991, 14: 69-72.

-

Rogers RW: A protection motivation theory of fear appeals and mental attitude modify. J Psychol. 1975, 91: 93-114.

-

Maddux JE, Rogers RW: Protection motivation and cocky-efficacy: A revised theory of fear appeals and mental attitude change. J Exp Soc Psychol. 1983, 19: 469-479. x.1016/0022-1031(83)90023-nine.

-

Floyd DL, Prentice-Dunn S, Rogers RW: A meta-analysis of research on protection motivation theory. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2000, 30: 407-429. 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2000.tb02323.x.

-

Bandura A: Health promotion from the perspective of social cognitive theory. Understanding and changing health behaviour: From health beliefs to self-regulation. Edited past: Norman P, Abraham C, Conner M. 2000, Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers, 299-339.

-

Bandura A: Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 2004, 31: 143-164. ten.1177/1090198104263660.

-

Keller C, Fleury J, Gregor-Holt N, Thompson T: Predictive power of social cerebral theory in exercise research: An integrated literature review. J Knowl Synth Nurs. 1999, 6: [http://www.des.emory.edu/mfp/KellerEtAl1999.pdf]

-

Stone D: Social Cognitive Theory. 1999, Accessed 14th March 2006, [http://hsc.usf.edu/~kmbrown/Social_Cognitive_Theory_Overview.htm]

-

Fishbein M, Ajzen I: Belief, mental attitude intention and behaviour: An introduction to theory and research. 1975, Menlo Park: Addison-Wesley

-

Sutton S: Theory of planned behaviour. Cambridge handbook of psychology, health and medicine. Edited by: Baum A, Newman Due south, Weinman J, West R, McManus C. 1997, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 177-179.

-

St Claire L: Rival Truths: Common sense and social psychological explanations in health and illness. 2003, Hove: Psychology Printing

-

Hardeman W, Johnston M, Johnston DW, Bonetti D, Wareman NJ, Kinmonth AL: Application of the theory of planned behaviours in behaviour change interventions: A systematic review. Psychol Health. 2002, 17: 123-158. ten.1080/08870440290013644.

-

Godin One thousand, Kok Thousand: The theory of planned behavior: A review of its applications to health-related behaviours. Am J Health Promot. 1996, xi: 87-98.

-

Armitage CJ, Conner G: Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analytic review. Br J Soc Psychol. 2001, 40: 471-499. 10.1348/014466601164939.

-

Mullen PD, Hersey JC, Iverson DC: Health behavior models compared. Soc Sci Med. 1987, 24: 973-981. x.1016/0277-9536(87)90291-7.

-

Fisher JD, Fisher WA: Changing AIDS-hazard behaviour. Psychol Bull. 1992, 11: 455-474. 10.1037/0033-2909.111.three.455.

-

Fisher JD, Fisher WA, Amico KR, Harman JJ: An information-motivation-behavioral skills model of adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Health Psychol. 2006, 25: 462-73. 10.1037/0278-6133.25.4.462.

-

Amico KR, Toro-Alfonso J, Fisher JD: An empirical examination of the information, motivation and behavioral skills model of antiretroviral therapy adherence. AIDS Intendance. 2005, 17: 661-73. x.1080/09540120500038058.

-

Leventhal H, Leventhal EA, Schaefer PM: Vigilant coping and health behaviour. Aging wellness and behaviour. Edited by: Ory MG, Abeles RD, Lipman PD. 1992, Newbury Park: Sage, 109-140.

-

Edgar KA, Skinner TC: Illness representations and coping as predictors of emotional wellbeing in adolescents with Type I diabetes. J Pediatr Psychol. 2003, 28: 485-493. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsg039.

-

Benyamini Y, Gozlan M, Kokia E: On self-regulation of a health threat: Cognitions, coping and emotions among women undergoing treatment for fertility. Cognit Ther Res. 2004, 28: 577-592. ten.1023/B:COTR.0000045566.97966.22.

-

Leventhal H, Meyer D, Nerenz D: The common sense representation of illness danger. Contributions to medical psychology. Edited by: Rachman Southward. 1980, Oxford: Pergamon Printing, 2: 7-30.

-

Sutton S: A critical review of the transtheoretical model practical to smoking abeyance. Understanding and changing health behaviour: From health behavior to cocky-regulation. Edited past: Norman P, Abraham C, Conner M. 2000, Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers, 207-225.

-

Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC: Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. Journal of Consult Clin Psychol. 1983, 51: 390-395. 10.1037/0022-006X.51.3.390.

-

Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcross JC: In search of how people change: Applications to addictive behaviours. Am Psychol. 1992, 47: 1102-1114. 10.1037/0003-066X.47.nine.1102.

-

Prochaska JO: Strong and weak principles for progressing from precontemplation to action on the basis of twelve problem behaviours. Wellness Psychol. 1994, 13: 47-51. 10.1037/0278-6133.thirteen.1.47.

-

Prochaska JO, Velicer WF, DiClemente CC, Fava J: Measuring processes of alter: Applications to the cessation of smoking. Periodical of Consult Clin Psychol. 1988, 56: 520-528. 10.1037/0022-006X.56.4.520.

-

Sutton South: Transtheoretical model of behaviour change. Cambridge handbook of psychology, wellness and medicine. Edited past: Baum A, Newman Due south, Weinman J, West R, McManus C. 1997, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 180-182.

-

Riemsma RP, Pattenden J, Bridle C, Sowden AJ, Mather L, Watt IS, Walker A: Systematic review of the effectiveness of phase based interventions to promote smoking cessation. Br Med J. 2003, 326: 1175-1177. 10.1136/bmj.326.7400.1175.

-

Marshall SJ, Biddle SJH: The transtheoretical model of behaviour change: A meta-analysis of applications to physical activity and exercise. Ann Behav Med. 2001, 23: 229-246. x.1207/S15324796ABM2304_2.

-

Weinstein ND: Testing 4 competing theories of health-protective behaviour. Health Psychol. 1993, 12: 324-333. x.1037/0278-6133.12.4.324.

-

Ashing-Giwa Yard: Health behaviour modify models and their socio-cultural relevance for breast cancer screening in African American women. Women Health. 1999, 28: 53-71. x.1300/J013v28n04_04.

-

Singh JA, Upshur R, Padayatchi N: XDR-TB in South Africa : No time for denial or complacency. PLOS Medicine. 2007, iv: 19-25. x.1371/periodical.pmed.0040050.

-

Kok G, Schaalma H, Ruiter RAC, Van Empelen P: Intervention mapping: A protocol for applying health psychology theory to prevention programmes. J Health Psychol. 2004, ix: 85-98. x.1177/1359105304038379.

-

Oxman Advertising, Fretheim A, Flottorp S: The OFF theory of research utilization. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005, 58: 113-116. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.ten.002.

-

The Improved Clinical Effectiveness through Behavioural Research Group (ICEBeRG): Designing theoretically-informed implementation interventions. Implementation Science. 2006, 1: 4-10.1186/1748-5908-one-four.

-

Amico KR, Harman JJ, Johnson BT: Efficacy of antiretroviral therapy adherence interventions: A enquiry synthesis of trials, 1996 to 2004. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006, 41: 285-297. x.1097/01.qai.0000197870.99196.ea.

-

Abraham C, Norman P, Conner Grand: Towards a psychology of health-related behaviour change. Understanding and irresolute health behaviour: From health beliefs to self-regulation. Edited by: Norman P, Abraham C, Conner Grand. 2000, Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers, 343-369.

-

Weinstein ND, Rothman AJ: Commentary: Revitalizing research on health behaviour theories. Health Educ Res. 2005, 20: 294-297. 10.1093/her/cyg125.

-

Munro Due south, Lewin Due south, Smith H, Engel M, Fretheim A, Volmink J: Patient adherence to tuberculosis handling : a systematic review of qualitative research. PLoS Medicine (submitted, provisionally accepted, pending concluding determination).

-

Simoni JM, Frick PA, Pantalone DW, Turner BJ: Antiretroviral adherence interventions : A review of current literature and ongoing studies. Top HIV Med. 2003, eleven: 185-198.

-

Volmink J, Garner P: Directly observed therapy for treating tuberculosis. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006, 2

-

Davies P, Walker A, Grimshaw J: Theories of behaviour change in studies of guideline implementation. Proceedings of the British Psychological Gild. 2003, 11: 120-

-

Schedlbauer A, Schroeder K, Peters TJ, Fahey T: Interventions to amend adherence to lipid lowering medication. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2004, 4

-

Vermeire E, Wens J, Van Royen P, Biot Y, Hearnshaw H, Lindenmeyer A: Interventions for improving adherence to treatment recommendations in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2005, 2

-

Mills EJ, Nachega JB, Bangsberg DR, Singh South, Rachlis B, Wu P, Wilson M, Buchan I, Gill CI, Cooper C: Adherence to HAART : a systematic review of developed and developing nation patient-reported barriers and facilitators. PLoS Med. 2006, 3 (eleven): e438-x.1371/journal.pmed.0030438.

-

Farmer P: Social scientists and the new tuberculosis. Soc Sci Med. 1997, 44: 347-358. 10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00143-8.

-

Lewin S, Dick J, Zwarenstein G, Lombard CJ: Staff grooming and ambulatory tuberculosis treatment outcomes: A cluster randomized controlled trial in South Africa. Balderdash World Health Organ. 2005, 83: 250-259.

-

Mukherjee JS, Ivers L, Leandre F, Farmer P, Behforouz H: Antiretroviral therapy in resource-poor settings : decreasing barriers to admission and promoting adherence. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 43 (Suppl 1): S123-S126. 2006 Dec i

-

Lim WS, Low HN, Chan SP, Chen HN, Ding YY, Tan TL: Impact of a pharmacist consult clinic on a hospital based geriatric outpatient clinic in Singapore. Ann Acad Med. 2004, 33: 220-227.

-

Schaffer SD, Tian L: Promoting adherence: Effects of theory-based asthma education. Clin Nurs Res. 2004, xiii: 69-89. 10.1177/1054773803259300.

-

Tuldra A, Fumaz CR, Ferrer MJ, Bayes R, Arno A, Balague Grand, Bonjoch A, Jou A, Negredo E, Paredes Ruiz L, Romeu J, Sirera G, Tural C, Burger D, Clotet B: Prospective randomised ii-arm controlled report to determine the efficacy of a specific intervention to ameliorate long-term adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000, 25: 221-228. 10.1097/00042560-200011010-00003.

-

Armitage CJ, Conner M: Reducing fat intake: Interventions based on the theory of planned behaviour. Changing wellness behaviour. Edited past: Rutter D, Quine L. 2002, Buckingham: Open Academy Printing, 87-104.

-

Theunissen NCM, de Ridder DTD, Bensing JM, Rutten GEHM: Manipulation of patient-provider interaction: discussing illness representations or action plans concerning adherence. Patient Educ Couns. 2003, 51: 247-258. 10.1016/S0738-3991(02)00224-0.

-

Aveyard P, Cheng KK, Almond J, Sherratt E, Lancashire R, Lawrence T, Griffin C, Evans O: Cluster randomised controlled trial of expert system based on the transtheoretical ("stages of change") model for smoking prevention and cessation in schools. BMJ. 1999, 319 (7215): 948-53.

Pre-publication history

-

The pre-publication history for this newspaper tin be accessed here:http://world wide web.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/7/104/prepub

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to admit the Norwegian Wellness Services Enquiry Centre, the GLOBINF Network, the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and the Constructive Health Care Research Programme Consortium of the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine for supporting Salla Munro during the grooming of this article. We would also similar to thank Judy Dick and Sheldon Allen for their comments on drafts of this review; Sylvia Louw, Anna Gaze, and Joy Oliver for their administrative support; and Simon Goudie for his editing of the paper.

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding writer

Boosted information

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they accept no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

JV and SL adult the idea for this paper, SM performed all searches and compiled the text, SL contributed to the writing and SL, TM and JV provided conceptual and editorial input. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Authors' original submitted files for images

Rights and permissions

This article is published nether license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Admission article distributed under the terms of the Creative Eatables Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Reprints and Permissions

About this commodity

Cite this article

Munro, Southward., Lewin, Southward., Swart, T. et al. A review of health behaviour theories: how useful are these for developing interventions to promote long-term medication adherence for TB and HIV/AIDS?. BMC Public Health vii, 104 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-7-104

-

Received:

-

Accustomed:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-7-104

Keywords

- Health Behaviour

- Behaviour Change

- Health Belief Model

- Adherence Behaviour

- Transtheoretical Model

Source: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2458-7-104

0 Response to "The Science and Art of Using Health Behavior Theories Reflectã¢ââ¦"

Post a Comment